This week’s blog post comes from the lovely Iain McDonald who is module leader for Research Methods.

Introduction: what is methodology?

All methodologies represent a standpoint on the task of research – it guides the researcher on a variety of questions, such as: ‘why am I researching?’, ‘what should I research?’, and ‘how should I carry out my research?’

All methodologies represent a standpoint on the task of research – it guides the researcher on a variety of questions, such as: ‘why am I researching?’, ‘what should I research?’, and ‘how should I carry out my research?’

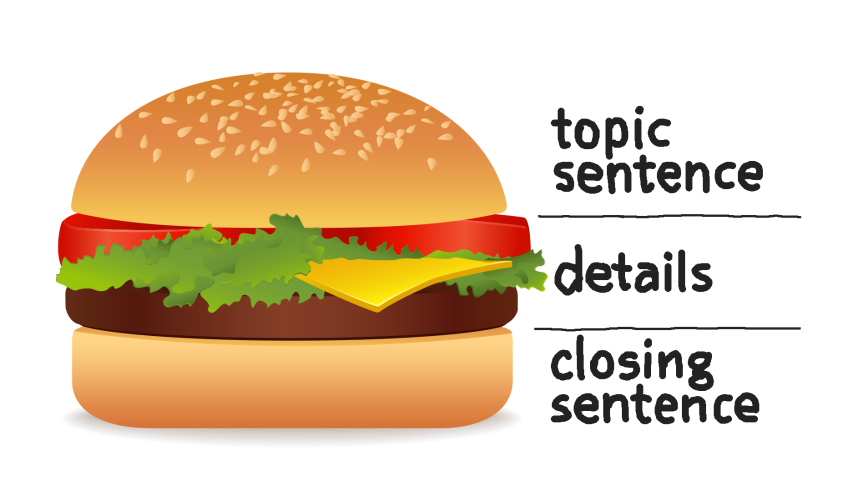

Being able to articulate methodology helps you to plan a more coherent and focussed research project – and helps to avoid the risk of trying to do too many things at once!

Why adopt a feminist methodology?

As a starting point, feminism can be located within a critical approach to research.[1] This means that it usually identifies its purpose as political in nature, meaning that research is carried out wit the purpose of seeking change in society and greater equality for particular groups within society, whether they be categorised by race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, religion or age. The particular focus of feminism means that their work is ultimately focussed on improving the position of women in society or before the law.

What can I research?

A feminist methodology will also naturally direct the researcher towards the investigation of legal issues and their effects on women – in method terms, this is sometimes referred to as ‘asking the woman question’.[2] However, it is important to remember that this does not mean that feminist research is only limited to looking at women – remember that researching other groups, such as men, or children, or institutions, all might help to shed light on the experiences of women.

What does a feminist methodology mean for the conduct of research?

While the focus of research is what tends to distinguish feminist legal research (and feminist methodology) from other forms of legal research, one of the most important and ongoing contributions of feminism to our understanding of the research process has been the way it acts as a critique and revision of traditional models and methods of research. While there are a number of issues that could be explored, let’s just take one for now:

The feminist critique of objectivity

Feminism is sceptical of objectivity in research. This scepticism comes from women’s own experience of research, whether it is legal or from some other discipline. There has been a long standing tradition in research whereby women have been either ignored as a distinctive group, or simply subsumed within a more general claim about ‘society’ or ‘mankind’, regardless of whether their experiences differ from those of men. This has often meant that women’s voices and needs have been overlooked or, at worst, excluded from wider social attention. (Conversely, where women have been targeted by research, it has often been as a problematic group, such as ‘bad mothers’, ‘single parents’, or ‘women who commit crimes’.)

Feminists critique such research because, while it claims a universal applicability within objectively carried out research, the reality is that these choices reveal a particular partial or subjective viewpoint that either views women and their experiences as insignificant in their differences, identical to those of men, or simply uninteresting. As a result, claims to objectivity must be treated with caution, as all research (and this would naturally include feminist research) emerges from particular viewpoints, assumptions and values.

So why research?

This critique might be seen as fatal to the idea of research at all!

However, being sceptical of objectivity does not mean the acceptance of a complete moral relativism.

Being sceptical of objectivity means that a feminist researcher becomes more critical and questioning in respect of all research, including its own. It allows us to interrogate the research we read and more critically evaluate our own:

Why this focus?

Why these questions?

Why these questions?

Why these methods?

Being sceptical about objectivity does not mean that all knowledge is rejected – instead it demands that we consider all claims to knowledge and truth within the context in which they are created.

Conclusion

There are many issues raised by feminist research and the use of feminist methodologies. Feminism challenges us to think about whether we approach our research with a set of assumptions, values or biases – and what the significance of this might be. For many of you, this may be the first time in your education that you have been asked to think about feminism. But whether or not you are interested in researching legal issues and their impact upon women, this methodology still has lessons to impart on how we can all research more effectively.

[1] See Matt Henn, Mark Weinstein and Nick Foard, A Critical Introduction to Social Research, (2nd edn, Sage 2009), Ch 2.

[2] Katherine Bartlett, ‘Feminist Legal Methods’ in M.D.A. Freeman, Lloyd’s Introduction to Jurisprudence, (9th edn. Sweet & Maxwell 2014), Ch 14 ‘Feminist Jurisprudence’.